4 Everything is smooth

Simple is beautiful

Mathematics and education

I should start by warning the reader that this blog post is probably one of the most opinionated and controversial ones I’ve written in this series until now. I will not compromise on this in any way because I deeply feel that what I am going to say is fundamental for the pursuit of our understanding of the Kosmos and the foundations of mathematics, philosophy and reasoning in general.

First, let’s begin by getting something straight. It’s a very shocking fact that all my readers have most probably never atttended a single mathematics class and don’t even know what mathematics is about. In my case, in Canada, I had to wait until university to attend my first “real” math class.

Before that, all of my “math classes” were basically about learning formulas by heart, without having a clue about where they come from or why they should be true, and applying them relentlessly to solve repetitive problems that came from nowhere and went nowhere. All of my “math” teachers prior to university also had no clue about what math is because they had never attended an actual math class themselves. This may sound radical, but ask any professional mathematician or anyone who took classes in a mathematics department in a university, and they will corroborate this fact.

I am almost crying when I think about this, because it’s a real pity that this wonderfully deep and beautiful subject is totally out of the scope of the modern education curriculum. This tragedy isn’t limited to children, whose heads we fill with empty knowledge and nonsensical crap, and who are misguided into thinking it’s math. Think about engineers and scientists. Their math classes at university never touched anything close to what I call real mathematics either. Even if they are taught very advanced concepts like calculus, they never get the chance to learn where all these formulas come from, or why they could possibly be true and useful.

It is no surprise to me that “mathematics” is hated as a subject. The way it is taught simply has practically nothing to do with what I call mathematics. So, if you hated math in school, there is still hope… You actually hated a crappy false representation of math.

To be totally transparent, let me state some exceptions to the general statements I expressed above. First, it wasn’t always this way. The students of Pythagoras and Euclid were most probably learning and practicing real math. Also, if you’ve been asking yourself some mathematical questions and tried to solve them by yourself, without reading about pre-made answers in some textbook, you most probably touched a bit of what math is about. So, let’s quickly describe the true nature of mathematics.

So, what is mathematics?

It’s not an easy task to introduce you to the true nature of mathematics. To do so, let me borrow a metaphor that one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, Alexandre Grothendieck, expressed in his memoirs:

As I’ve often said, most mathematicians take refuge within a specific conceptual framework, in a “Universe” which seemingly has been fixed for all time - basically the one they encountered “ready-made” at the time when they did their studies. They may be compared to the heirs of a beautiful and capacious mansion in which all the installations and interior decorating have already been done, with its living-rooms , its kitchens, its studios, its cookery and cutlery, with everything in short, one needs to make or cook whatever one wishes. How this mansion has been constructed, laboriously over generations, and how and why this or that tool has been invented (as opposed to others which were not), why the rooms are disposed in just this fashion and not another - these are the kinds of questions which the heirs don’t dream of asking . It’s their “Universe”, it’s been given once and for all! It impresses one by virtue of its greatness, (even though one rarely makes the tour of all the rooms) yet at the same time by its familiarity, and, above all, with its immutability.

Alexandre Grothendieck, “Récoltes et semailles” [1]

So, math is about building that mansion with your own hands (playing the roles of the architect, the mason, the carpenter, …), not just about learning about pre-made tools (like a hammer, a drill, a saw … i.e. arithmetic, algebra, calculus, geometry…). Mathematics is about asking the right questions and creating the tools to solve them appropriately. Mathematics is all about creativity, imagination, and the beauty and simplicity of how all of the different parts fit together. It’s about how we can continuously rebuild the mansion in a more effective way, by using or creating the right tools to assemble the structure, putting in the right furnishings, and doing some kind of Feng Shui of that conceptual exploration.

Math is about thinking in a formal way, assembling ideas piece by piece into a construction; it’s a journey into the explorations of conceptual thought. Math is about beauty, a grasp of the Tao, the unattainable and unnameable intuition of The One, the Way.

The room called “Calculus”

The rest of this essay will be dedicated to giving you your “first math course” 😆. For that, I’ll give you a quick tour of a room that is usually referred to as calculus. But to really give you a taste of what that room is like, we will not content ourselves with a simple tour. I will try to make you think about the foundations of calculus by presenting a different room than the one you were possibly introduced to, if you ever learned about calculus. If you were never taught calculus, then you are very lucky because this alternative presentation of the subject will get you up to speed in ways that would benefit even professional mathematicians.

In some ways, this alternative presentation of calculus is much closer to the intuitions of the original inventors of the room: Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz. Unfortunately, those intuitions were discarded along the way, and the room was rebuilt (with the wrong tools) in a very complex and intricate fashion. The reason for this reconstruction was the supposedly lack of rigor behind those intuitions. Because of this, calculus nowadays is only formally taught to specialized mathematicians. To everybody else, we teach calculus by just dropping them the formulas and evacuating all the fundamental questions like the whys and the hows.

For that reason, understanding calculus and its foundations is somehow unattainable knowledge, and this beautiful room filled with precious tools is given as is; a prebuilt room in which you shouldn’t ask too many questions because practically no one knows why or how anymore.

Infinitesimal numbers

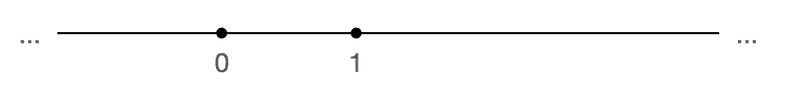

For the sake of the discussion that follows we need to imagine a line $R$ and with two fixed distinct arbitrary points chosen on it: $0$ and $1$.

It is possible to define operations on the points of $R$ such as additions ”$+$” and multiplications ”$\cdot$” in a purely geometrical way using a ruler and compass. I will not define those here, but you can think of them as the usual sum of numbers and multiplication of numbers on the real $\mathbb{R}$ line. The structure $(R,0,1,+,\cdot)$ satisfies the properties of a commutative ring.

Here are the properties that a (commutative) ring must satisfy.

Definition 1: A ring is a set $R$ equipped with two binary operations $+$ and $\cdot$ that satisfy (for all $a,b,c\in R$): \begin{equation} a+(b+c)=(a+b)+c \end{equation} \begin{equation} a+b=b+a \end{equation} \begin{equation} \textrm{There exists an element}\quad 0\in R\quad\textrm{such that}\quad 0+a=a \end{equation} \begin{equation} \textrm{There exists an element}\quad -a\in R\quad\textrm{such that}\quad a+(-a)=0 \end{equation} \begin{equation} a\cdot (b\cdot c)=(a\cdot b)\cdot c \end{equation} \begin{equation} \textrm{There exists an element}\quad 1\in R\quad\textrm{such that}\quad 1\cdot a=a\cdot 1=a \end{equation} \begin{equation} a\cdot(b+c)=a\cdot b + a\cdot c \end{equation} \begin{equation} (a+b)\cdot c=a\cdot c + b\cdot c \end{equation} When the multiplication $\cdot$ is commutative i.e. $a\cdot b=b\cdot a$ we say that the ring is commutative.

So we see that a ring behaves very much like normal integers $\mathbb{Z}$ or real numbers $\mathbb{R}$.

The real numbers $\mathbb{R}$ (and complex numbers $\mathbb{C}$) have an extra property that makes it what we call a field: all elements $r\in\mathbb{R}$ except $0$ i.e. $r\neq 0$ have a multiplicative inverse $r^{-1}$ (also written $1/r$) such that $r\cdot r^{-1}=1$. Lets not assume that this is true for $R$ (i.e. $R$ is just a ring not a field).

Now, let’s define the subset of infinitesimal numbers on $R$.

Definition 2: An infinitesimal number $d$ is a member of the set: \begin{equation} D=\{ d\in R | d^2=0 \}

\end{equation} We also call elements of $D$ nilpotent elements.

Most mathematicians will be shocked by such a definition because their brains are wired to think that, when $d^2=0$, we can conclude that $d=0$. More generally, one of the first results we prove in the field of real numbers $\mathbb{R}$ is

\begin{equation} a\cdot b=0 \Rightarrow a=0\quad \textrm{or}\quad b=0\quad\quad (P) \end{equation}

But let’s look more closely at this proof and “refute it,” in our context. The proof starts by assuming that the conclusion is false, i.e. $a\neq 0$ and $b\neq 0$, and concludes that this leads to a contradiction, as follows. Since $a\neq 0$, it has a multiplicative inverse $a^{-1}$ such that $a\cdot a^{-1}=1$ (because, here, $\mathbb{R}$ is a field). And then you can proceed as follows:

\begin{align} a\cdot b = 0 &\Rightarrow a^{-1}\cdot(a\cdot b)=a^{-1}\cdot 0 \\ &\Rightarrow (a^{-1}\cdot a)\cdot b = 0 \\ &\Rightarrow 1\cdot b = 0 \\ &\Rightarrow b=0 \end{align}

which is a contradiction, since we presumed that both $a\neq 0$ and $b\neq 0$ in the first place. A classical mathematician would argue that this is valid proof of ($P$). This is only partially true… The main problem with this proof is that is uses the law of excluded middle and the technique of proof by contradiction to establish the truth of a proposition. This technique goes as follows. We want to prove $P$. To do so, we assume $\neg P$ (not P) and derive a contradiction so that, by the logical law of excluded middle,

\begin{equation} P\vee \neg P=\top \end{equation}

(either $P$ or $\neg P$ is true) we conclude that $P$ must be true.

This technique of proof, using the principle of excluded middle, was criticized at the beginning of the 20th century by a group of mathematicians called the intuitionists, and for good reason. Not only did it destroy the notion of infinitesimals, as we saw above, but it also brought very counter-intuitive statements into the theory.

Since there is an incompatibility between the existence of the non-trivial subset $D$ of infinitesimals and the logical law of excluded middle, in the rest of this essay, we will, like the intuitionists, leave the law of excluded middle aside and not use it. This leaves room for the infinitesimals $D$ to be a valid non-trivial concept.

This is one of the crucial points we wish to convey in this essay. The law of excluded middle basically wipes away many very interesting mathematical creatures. This law can be considered philosophically incompatible with Taoism, which states that the Tao, the source Truth, is unknowable as a whole. You cannot prove that $P$ is true just because $\neg P$ is false. The validity of $P$ is still part of the unknowable. A very small subset of modern mathematicians, like the ones who studied categorical logic, are aware of this. They know that principles like the excluded middle are only true in some very specific universes, such as the universe of sets (which form a Boolean topos). Although the universe of sets is a nice room in the big mansion of mathematics (to paraphrase Grothendieck), it is far from being the most interesting one. The universe of sets has a trivial (degenerate) logic called Boolean logic that has only two possible truth values: true or false. Classical mathematicians, who undoubtedly comprise more than 98% of all current professional mathematicians, are stuck in that room and they blindly reject the existence of the other rooms in the mansion and refuse to visit them. In the rest of this essay, I will try to show why they are wrong to limit themselves to that specific room. By doing so, they are throwing away most of their chances of solving some the greatest mysteries of the Kosmos, and of getting a glimpse of parts of the unknown.

An assymetry of intuitionistic logic

If you think about it, the infinitesimals $d\in D$ can’t have multiplicative inverses $d^{-1}$. The reason for this is that, if they did, we would have:

\begin{align} d^2=0 & \Rightarrow d\cdot d=0 \\ & \Rightarrow d^{-1}\cdot(d\cdot d)=d^{-1}\cdot 0 \\ & \Rightarrow (d^{-1}\cdot d)\cdot d = 0\\ & \Rightarrow 1\cdot d=0\\ & \Rightarrow d=0 \end{align}

which is a contradiction, since $0$ can never have a multiplicative inverse (since nothing times $0$ can give you $1$ [because we assumed $0\neq 1$ from the very beginning]).

But wait!!! Wasn’t that proof by contradiction? We came up with a hypothesis, derived a contradiction from it, and we concluded that our hypothesis was false. A classical mathematician could argue that we used the same technique as we did before, but, in reality, there is an important distinction to be made here. For intuitionists, proving that something is false because it leads to a contradiction is all good–it’s called “proof of negation.” This kind of proof doesn’t use the excluded middle principle. Because contradictions are generally not tolerated in math (because they not only mean trouble, from them you can derive whatever proposition, whether it is absurd or not). So for intuitionists, the law of non-contradiction, \begin{equation} P\wedge \neg P=\bot \end{equation} which states that $P$ and $\neg P$ cannot both be true, is a valid law. But its dual, the law of excluded middle, is not true in general. This is a fundamental asymmetry in the laws of intuitionistic logic.

So, intuitionists actually use the above technique to prove the negation of some $P$ propositions, i.e. $\neg P$. On the contrary, they don’t accept proof of a $P$ proposition that starts by assuming that $P$ is false, i.e. $\neg P$, and deriving from it a contradiction, because this doesn’t actually prove $P$. It is, in fact, a proof of $\neg\neg P$.

For Aristotle and classical mathematicians, $\neg\neg P=P$, but not for intuitionists!

In our room, we picked intuitionistic logic as the fundamental logic. In fact, in any topos, the rules of intuitionistic logic are true. In some topos, we have more rules, like in the topos of sets where the excluded middle law applies and the logic is reduced to be Boolean. But these are exceptions, unless you want to stay confined in the rooms with Boolean logic (like the universe of sets).

The derivative

So, we are visiting a new room in the mansion. In this room, we are replacing the classical set of real numbers $\mathbb{R}$ by the more general ring $R$ of the geometrical line and rejecting the law of excluded middle (as a general law). We can begin the tour by specifying the type of room we are in even further. For this, we will state that, in this specific room, the following axiom is valid:

Axiom 1: Take any $g:D\rightarrow R$, for all $d\in D$ there exists a unique $b\in R$ such that $g(d)=g(0)+b\cdot d$.

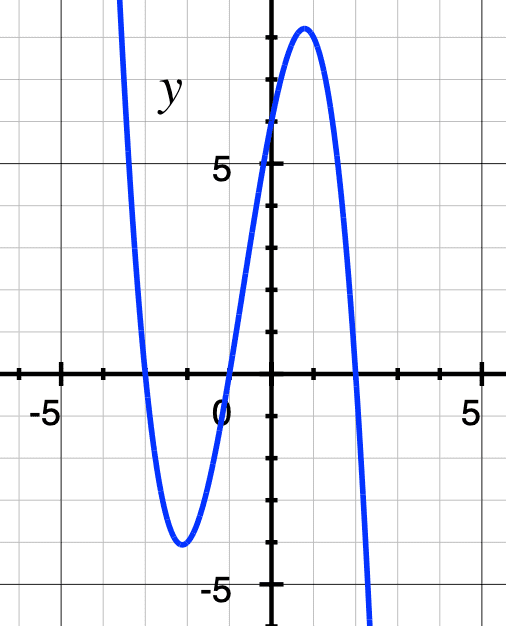

To give you an intuitive understanding of what this means, consider a $h:R\rightarrow R$ function. This function assigns a $h(r)\in R$ point to any $r\in R$ point. Visually speaking, this $h$ is drawn as a curve on the $R\times R$ plane:

These curves are very interesting to study because they arise everywhere in nature. When we throw a ball in the air, for example, it follows such a curve. To study the physics of throwing balls or the motion of planets, we need to study these curves and their properties. Newton and Leibnitz invented a powerful tool to do so: calculus.

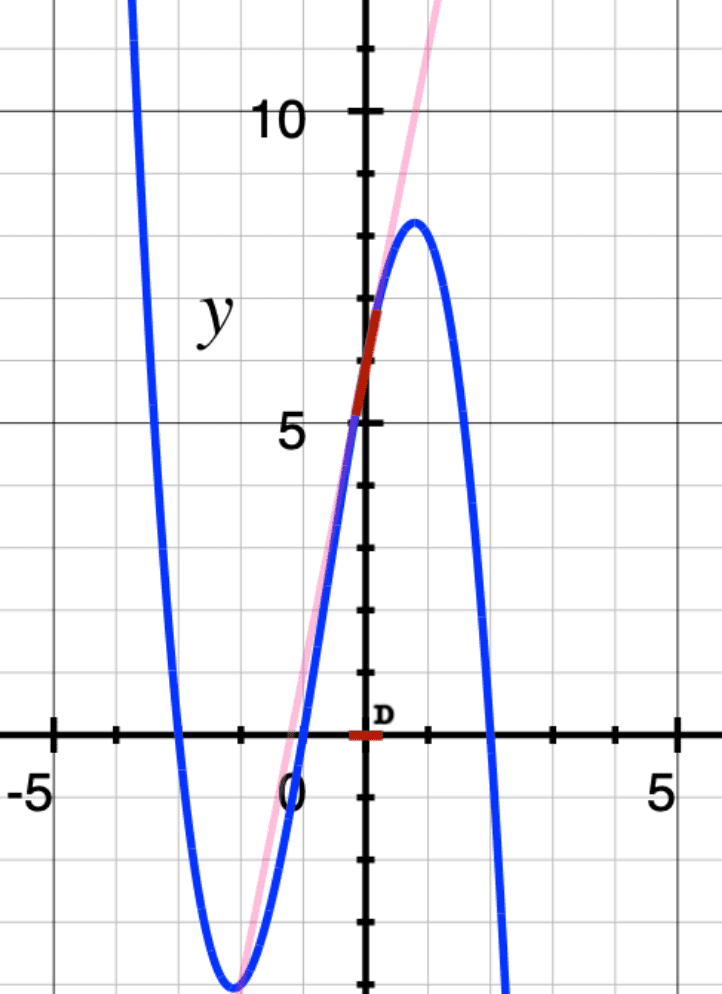

Axiom 1 states that, over the sets of $D$ infinitesimals, there is a unique $b\in R$, such that $h(d)=h(0)+b\cdot d$ for any $d\in D$. So, any $h:R\rightarrow R$ is a linear function on the $D\subset R$ subset. The unique $b\in R$ is called the slope of the line that coincides with $h$ over $D$. Visually speaking, it looks like this:

So, on the set of $D$ infinitesimals, closely packed around $0$, any curve (in blue) can be thought of as a small portion (in red) of a straight line (in pink).

The following proposition is a direct consequence of Axiom 1. It lets us do the same approximation of $h$ by a line segment around any infinitesimal neighbourhood of an arbitrary point $x\in R$.

Proposition 1: For any curve $f:R\rightarrow R$ and any $x\in R$ we have a unique $b\in R$ such that for whatever $d\in D$: \begin{align} f(x+d)=f(x)+b\cdot d \end{align} We have a special name for this $b$ that depends on $x$: we call it $f'(x)$ and name it the derivative of $f$ at $x$, thus we write: \begin{align} f(x+d)=f(x)+f’(x)\cdot d \end{align}

The proof of proposition 1 is pretty easy. Suppose $f:R\rightarrow R$ is an arbitrary curve. Define $g:R\rightarrow R$ as follows: $g(y)=f(x+y)$. By Axiom 1, for any infinitesimal $d\in D$, we have a unique $b\in R$, such that $g(d)=g(0)+b\cdot d$, i.e. $f(x+d)=f(0+d)+b\cdot d$, i.e. $f(x+d)=f(x)+b\cdot d$, as we wanted.

Proposition 1 basically establishes that, in our room, any $f:R\rightarrow R$ curve is differentiable everywhere, i.e. all curves are smooth everywhere in our room! This is certainly a remarkable fact that will challenge the intuition of classical mathematicians stuck in the room of sets. In (the topos of) sets, we can construct very peculiar $f$ functions, some being non-smooth at certain points, or even non-smooth at every point. For example, take the following $f:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}$ function, defined as follows: \begin{equation} f(x) = \begin{cases} 0 & x\neq 0 \\ 1 & x=0 \end{cases} \end{equation} The function is not “smooth” at $x=0$ (it does a little jump). But this kind of definition uses the law of excluded middle to define $f$ everywhere in $\mathbb{R}$, because it assumes that for any $x\in\mathbb{R}$ we have either $x=0$ or $x\neq 0$. In our special room, we don’t have this possibility. For example, if we take an infinitesimal $x\in D$, we really can’t tell if $x=0$ or not (these are so small).

Basic rules for derivatives

Now, let’s exploit the power of those infinitesimal numbers to derive the usual rules for the derivative.

Theorem 1: Let $f,g:R\rightarrow R$ and $r\in R$, we have:

- $(f+g)'(x)=f'(x)+g'(x)$

- $(r\cdot f)'(x)=r\cdot f'(x)$

- $(f\cdot g)'(x)=f'(x)\cdot g(x) + f(x)\cdot g'(x)$

- $(f\circ g)'(x)=f'(g(x))\cdot g'(x)$

The rigorous proof of Theorem 1, in the usual room of classical mathematics, is pretty laborious. Even just the rigorous definition (often called $\varepsilon-\delta$ definition) of derivative is very laborious to grasp and isn’t presented to students of calculus unless they are specializing in pure math, and only at the university level of education. Nevertheless, in our special calculus room, where infinitesimals exists, this proof is so trivial and direct that any high-school student is able to follow it. With the power of infinitesimals, we reduce the complexity of calculus (and differential geometry) to simple high school algebra calculations.

We will need a preliminary result to establish this theorem.

Lemma 1: For any $r_1,r_2\in R$, if for all $d\in D$ we have that $d\cdot r_1=d\cdot r_2$ then we can conclude that $r_1=r_2$

To prove that we define $g(d)=r_1\cdot d$, then, by Axiom 1 we have that there exists a unique $b\in R$, such that $g(d)=g(0)+b\cdot d$, i.e. $g(d)=r_1\cdot 0+b\cdot d=b\cdot d$. But since we already had $r_1\cdot d=r_2\cdot d$ and this $b$ must be unique, we can therefore conclude, as we had wished to prove, that $r_1=b=r_2$.

This is an interesting property because, as we saw earlier, infinitesimals are not invertible, which means that their inverse cannot be used to cancel them on each side of the equation. Yet, when the equation is true for all $d\in D$, then we can remove the $d$ on each side.

Now, the proof of Theorem 1 is straightforward. Let’s show the first and last statements of Theorem 1 (I’ll leave the second and third ones for you as an exercise).

\begin{align}

(f+g)(x+d) &= f(x+d)+g(x+d)\quad\textrm{(this is definition of}\quad f+g) \\

&= f(x)+f’(x)\cdot d+g(x)+g’(x)\cdot d \quad (\textrm{Proposition 1 applied to both}\quad f\quad\textrm{and}\quad g)\\

&= (f(x)+g(x))+(f’(x)+g’(x))\cdot d \quad (\textrm{associativity and distributivity in a ring})\\

&= (f+g)(x)+(f’(x)+g’(x))\cdot d \quad (\textrm{by definition of} \quad f+g)\\

&= (f+g)(x)+{(f+g)}^\prime(x)\cdot d \quad (\textrm{by definition, see Proposition 1})

\end{align}

So the last equation states that

\begin{equation}

(f+g)(x)+(f’(x)+g’(x))\cdot d=(f+g)(x)+{(f+g)}^\prime(x)\cdot d

\end{equation}

but then we can substract $(f+g)(x)$ on both sides so that we get:

\begin{equation}

(f’(x)+g’(x))\cdot d={(f+g)}^\prime(x)\cdot d

\end{equation}

and by Lemma 1, since this is valid for any $d\in D$, we can cancel the $d$’s on both sides, which yields the desired result.

Now, let’s look at the proof of the last one (also called the chain rule). \begin{align} (f\circ g)(x+d) &= f(g(x+d))\quad\textrm{(this is definition of}\quad f\circ g) \\ &= f(g(x)+g’(x)\cdot d) \quad (\textrm{Proposition 1 applied to}\quad g) \\ &= f(g(x))+f’(g(x))\cdot (g’(x)\cdot d) \quad\textrm (*)\\ &= f(g(x))+(f’(g(x))\cdot g’(x))\cdot d \quad\textrm{(associativity in ring)}\\ &= (f\circ g)(x)+(f\circ g)^\prime(x)\cdot d\quad\textrm{definition of}\quad (f\circ g)’ \end{align}

Where in (*) we applied proposition 1 to $f$ with $d'=g'(x)\cdot d\in D$ also being an infinitesimal since \begin{equation} d’^2=(g’(x)\cdot d)^2=(g’(x))^2\cdot d^2=(g’(x))^2\cdot 0=0 \end{equation}

Again, if we look at the last equation, we got \begin{equation} (f\circ g)(x)+(f’(g(x))\cdot g’(x))\cdot d = (f\circ g)(x)+{(f\circ g)}^\prime(x)\cdot d \end{equation} so by cancelling the terms $(f\circ g)(x)$ on both sides we get: \begin{equation} (f’(g(x))\cdot g’(x))\cdot d = {(f\circ g)}^\prime(x)\cdot d \end{equation} but by lemma 1 we can remove the $d$’s on both sides to achieve the result needed.

For our mathematicians readers, this is probably the most concise proof of those two results you’ve ever seen. For our non-mathematicians, it’s probably the only accessible formal proof that’s available to your full understanding. This proof is so short, straightforward, expeditious and intuitive that, in my opinion, it challenges all other methods of teaching calculus. This way of doing calculus with algebraic methods, with the use of infinitesimals, is called synthetic differential geometry. I will include more detailed references to these methods at the end of this post if you wish to study them more deeply.

Measuring the circle

Now, let’s continue our exploration of this special room and do something interesting with the notions of infinitesimals and derivative. If you recall, in high school, we were given the formula of the circumference of a circle with $r$ radius: the formula tells us that the circumference is $2\pi r$. Of course, you’ve probably never seen proof of that fact since it usually requires calculus techniques.

Well, again, with our infinitesimals, this fact becomes very easy to explain. The explanation won’t be as formal as the previous ones because I want to remain concise in this blog post. Notions like the length of a curve or the area of a surface, for example, will not be formally defined here for the sake of brevity. We will instead appeal to your intuition about these notions.

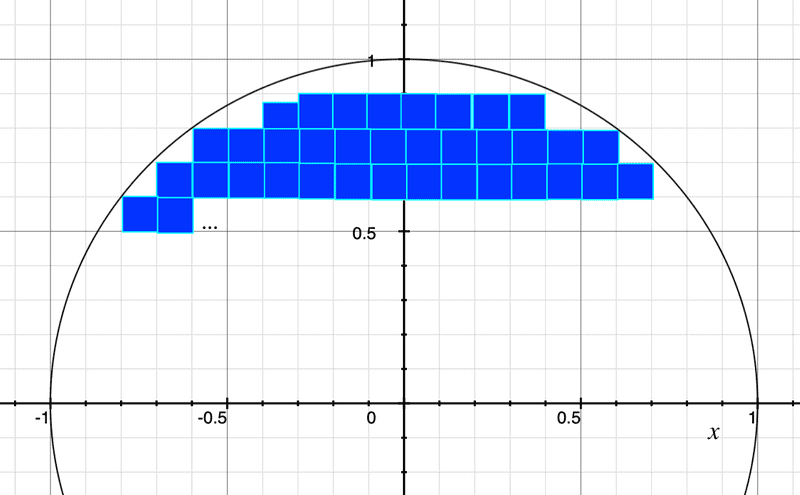

First, let’s define $\pi$ as being the area of the unit disc (disc with a $r=1$ radius). You can think of the notion of area by imagining the unit disc being filled with small squares, like the following picture suggests:

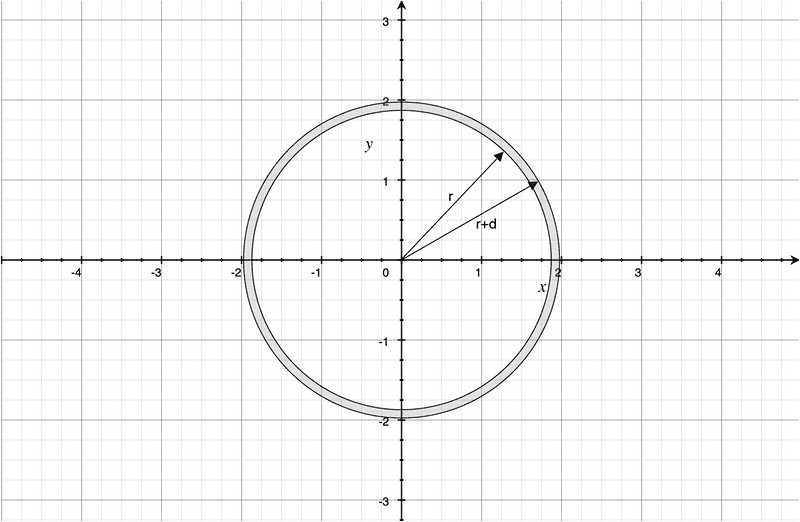

Let’s now take a circle of radius $r$. In what follows, we will call $C(r)$ the circumference of the circle with $r$ radius, and $A(r)$ the area enclosed by the circle. Let’s take the $r$ radius and make it vary by adding an infinitesimal $d\in D$ to it, as the following pictures shows:

Everything is smooth

The title of this post is a wink at the well-known spiritual motto, “Everything is connected.” In the context of synthetic differential geometry, as we saw above, all functions are differentiable everywhere so that all functions are smooth. The motivation for writing this post came to me through a kind of spiritual revelation during which I connected the dots between the cosmological insight I was experiencing in that moment, topos theory, logic, and my limited knowledge of synthetic differential geometry. Everything is smooth is a stronger metaphysical affirmation. It basically says that our reality is just superpositions of smooth fields of force. Any materialistic view of it is merely a misleading illusion.

For example, elementary particles are probably not particles, per se. We are taught to view atoms in this way:

These smooth force fields can best be understood using the tools of synthetic differential geometry. I strongly believe that physicists would benefit from using these tools to understand physics in a deeper way. I therefore also strongly believe that synthetic differential geometry gives humanity very powerful tools to unlock some of the deep secrets of the universe. I hope this blog post has helped you see that possibility.

References

Strangely enough, the main researchers that developed the field of synthetic differential geometry are all mathematicians that I personally met at one point or another during my Ph.D., including my Ph.D advisor, Gonzalo E. Reyes. This entire post is borrowed from their work. The reader can find a much more extensive presentation of the subject in the following references:

[1] William F. Lawvere, An outline of synthetic differential geometry, 1998 (PDF available online)

[2] Anders Kock, Synthetic Differential Geometry — Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, 2006

[3] Ieke Moerdijk, Gonzalo E. Reyes, Models for Smooth Infinitesimal Analysis, Springer New York, 1991