3 Excluded

Not letting Truth escape

To learn the way of awakening (Dao of Buddha) is to learn the self. To learn the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is the whole being realized. The whole being realized is to let the body-mind of the self and that of the other cast off. Further, the trace of the awakening ceases. Then, the traceless awakening illimitably advances forth.

“Dynamic Realization of Sempiternal Truth: Shobogenzo Genjo-Koan” Translation by Yasuhiko Genku Kimura

Where Magic lies

Where Magic dies

Not excluding the Yin inside the Yang

Not excluding the Yang inside the Yin

Plunging in this infinite recursive descent

Where the complexity of Truth lies never resolved

MAFA2022

What is logic?

We all have a unique relationship with this concept. For most of us, we decided to exclude this dry and arid world from our concerns and I totally understand this conscious or unconscious decision. In this article, I will ask you to revisit this and maybe expand the boundaries of your sense of its utility.

Let me first tell you how I view logic in simple concise terms.

We, humans, are collectively constructing an ideosphere where the “known” is assembled into concepts and those concepts relate with each other in some patterns. This ideosphere includes all knowledge: mathematical, scientific, metaphysical, spiritual knowledge… The language we use in the ideosphere to assemble all of it is what we call “logic”. It’s like a chess game but with propositions as the pieces and the operators and rules for the possible moves.

So you probably think I am overextending the application of the concept of logic… How could logic apply to spiritual knowledge, for example… Isn’t it that, in all major spiritual traditions, logic is something you have to drop at some point of your spiritual path? Yes, for sure! Logic lives in the ideosphere and this ideosphere is that thin layer of reality: knowledge is that evolutive yin force that counters the devolutive forces of entropy which turn order into chaos. As we know from Lao Tseu the unknowable part of reality is infinite and will always remain impossible to grasp entirely in the ideosphere. But, still, the ideosphere has infinite potential to grow. And logic is just a tool to make this exploration simpler and less prone to errors.

In this game of concepts and knowledge, the rules can be flexible too. The classical logic, a legacy of the Greeks, has to be revisited and extended with more flexibility. Flexibility to make it useful and faithful to the context of those concepts.

The conceptual shift I am proposing is to make Aristotle’s logic be a special case and rather than impose a universal logic that must apply to all situations, discover the natural logic of a given domain of knowledge and its rules.

In the next section, we will look at some classical laws that Aristotle proposed and begin questioning them in their universality.

Then, we will dig even deeper and explore the logic of a very specific conceptual universe: open sets of the plane for the Euclidean topology. The geometric nature of this subject will help us explain those concepts with the use of visual support.

The Excluded middle

The Greeks definitely had a great influence on logic. Particularly Aristotle, who formalized some basic principles of logic. Among the 3 laws that Aristotle proposes, the law of excluded middle states that either a proposition $P$ is true, or the negation of this proposition, not $P$ (denoted $\neg P$), is true (true is also denoted by the symbol $\top$), which can be written as the following equation:

$P\vee\neg P=\top$

In more human-friendly terms… The law of the excluded middle says that either something is true, or its contrary is true… All other possibilities are excluded. We already touched on this law in the previous posts. Now we are going to dig a bit deeper in this direction and try to demonstrate why it should not be a universal law. This law makes sense in some specific contexts, like arithmetic and sets. But in other contexts, like spirituality, psychology and linguistics, this law is not true and is not applicable.

In fact, this law probably doesn’t hold in any part of reality. Let’s take, for example, the concept of honesty. The law states that a person (for example) is either honest or not honest. We all know that, on the contrary, this is universally false… No person can be absolutely honest or absolutely not honest. The excluded middle law thus excludes the entire gray zone in between honest and not honest, the zone where everything in our existence lies.

Another principle of the logic of Aristotle that is not universally valid is the principle of non-contradiction. This principle seems to not be valid at the quantum level, as Lupasco pointed out in his quantum logic.

These two laws of Aristotle served us for many centuries, helping us in the discovery of particular fields. It is now time to transcend those two laws and make them into special cases instead. In what follows, I will attempt to demonstrate how dropping the universality of those a priori laws gives rise to a kind of richness that can greatly widen the scope of our ideosphere with a simplified view, and which is more faithful to reality.

Geometric logic

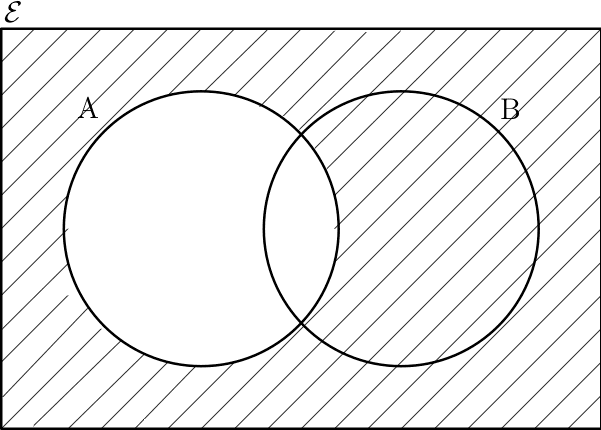

If you remember the first contacts you had with mathematical logic and sets, it probably contained usages of Venn diagrams, like the following:

Let’s revisit them, but with a different twist: the twist of geometric logic. For that, you will need a very quick introduction to the basics of topology. This will require you to jump into the abstractions of math but hang on… it won’t get too complex. Everything will be explained in pictures, don’t worry 😆

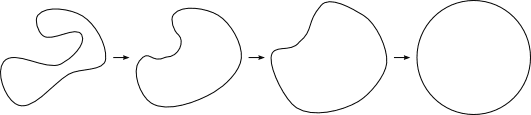

Topology is a part of mathematics that studies shapes, but in a different manner than high-school geometry. In high-school Geometry, roughly, two shapes are equivalent when you can rotate, translate or at the limit scale one of them to get the other. Because for elementary geometry, angles and distances are the important aspects of a figure. In Topology, the concept of equivalence is much more flexible: two shapes are equivalent if you can continuously morph (transform) one into the other. For example, here are some equivalent shapes:

To simplify, let’s consider shapes living in the Euclidean plane $\mathbb{R}^2$ (traditional 2-dimensional infinite plane). The discs $A$ and $B$ from Figure 1 are such shapes. They are subsets of $\mathbb{R}^2$, i.e. $A,B \subseteq \mathbb{R}^2$. Let’s look at them from the point of view of topology.

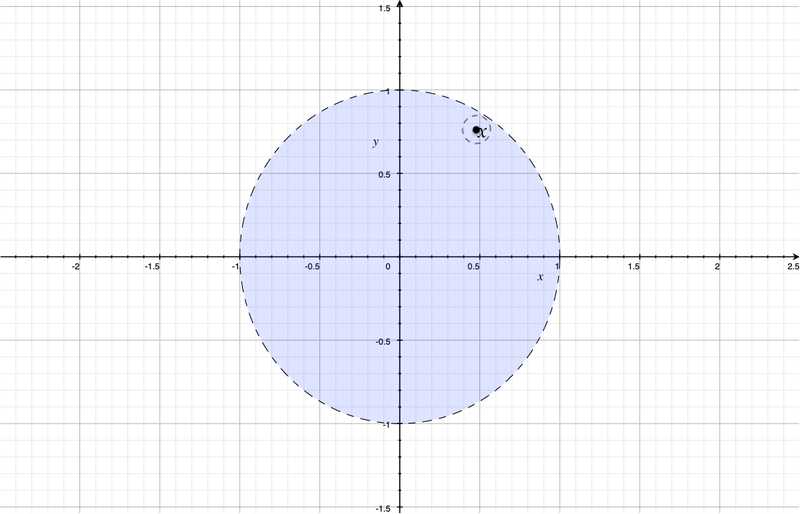

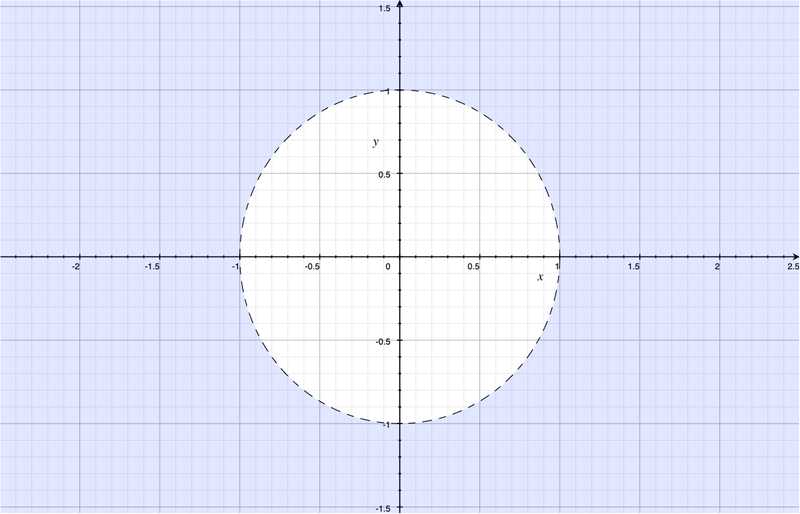

In topology, we are interested in two special kinds of subsets of a space: open subsets and closed subsets. The open sets of the Euclidean plane are subsets that have a specific property: around each point in an open set, $x\in O$, you can find a disc around that $x$ point that is totally contained in $O$. To clarify this, let’s look at the following example: the open unit disc is

$O=\{ (x,y)\in \mathbb{R}^2 \| x^2+y^2 < 1\}$

or, in a picture:

You can imagine picking any point $x$ inside the disc (not including the border unit circle), and you will always be able to find a small disc around $x$ that is completely contained inside the unit disc. You just have to pick a disc around $x$ that has a small enough radius to completely fit inside. For this reason, we call $O$ an open subset of $\mathbb{R}^2$.

The Shobogenzo Koan expresses this very nicely:

As a fish travels through the water, there is no end to the water, no matter how far it travels.

“Dynamic Realization of Sempiternal Truth: Shobogenzo Genjo-Koan” Translation by Yasuhiko Genku Kimura

Imagine the blue circle to be the water and that a bowl (the unit circle) contains it. The fish can never be at the unit circle because the bowl is there… And the fish cannot traverse the bowl. So, wherever the fish is inside the bowl, there will be a space containing water all around the fish. The water is an open subset.

Open subsets of the Euclidean plane $\cal{O}(\mathbb{R}^2)$ have very nice properties that we won’t prove here, namely:

- There is a smallest open subset: the empty set $\emptyset\subseteq \mathbb{R}^2$

- There is a largest open subset: $\mathbb{R}^2\subseteq \mathbb{R}^2$

- If $A$ and $B$ are open subsets, i.e. $A,B\in\cal{O}(\mathbb{R}^2)$, then their intersection $A\cap B\in\cal{O}(\mathbb{R}^2)$ is also open and their union $A\cup B\in\cal{O}(\mathbb{R}^2)$ are also open.

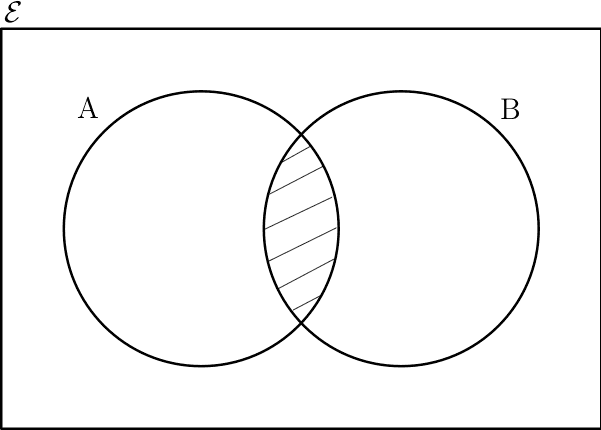

Now, let’s return to the Venn diagrams we started with. If you remember, when you learned about them when you were a kid, they were used to explain logic. If we had $A$ and $B$ the intersection, $A\cap B$ (see Figure 1) can be logically interpreted as ”$A$ and $B$”. The union $A\cup B$ is the logical equivalent of ”$A$ or $B$”. In logic, we also studied negation, such as not $A$ (usually denoted as $\neg A$). In a Venn diagram, this is pictured as

the complement of $A$. And the peculiar behaviour of this complement reflects the following logical principles, which clearly are Aristotle’s law:

- $A$ and not $A$ is always false (a contradiction)

- $A$ or not $A$ is always true (a tautology)

Now, if we consider studying only open subsets and make Venn diagrams with them, we may ask ourselves if those two rules are true in the context of open sets. We will use these two rules and explore their validity in this very specific universe.

We will use the term geometric logic to refer to all of the varieties of logic we encounter in our explorations. Here, geometry is used in its largest conceptual interpretation: as topology, projective geometry, Euclidean geometry are parts of the study of geometry. Hence, the logic of the Euclidean topology of the plan is a form of geometric logic. Let’s learn a bit about its nature.

What could be the negation of an open set $O$ be? Take the open unit disc of Figure 3. What would a good candidate for $\neg O$ be? It must be an open set (as defined above). Think about it. We cannot put a point lying on the unit disc in $\neg O$. Because in no way you can find a disc small enough to be completely within the limits of $O$: any disc around a point on the unit circle will always contain points inside $O$! So the boundary (the unit disc) is not within the $\neg O$. It seems pretty clear that the following candidate would be best:

How can we generally define this operator that lives in the universe of open subsets of the plane? One simple way of thinking about it to take all possible open sets $U$ that are outside of $O$: we will say that $U$ is outside of $O$ when $U\cap O=\emptyset$. If you unite all of those possibilities of being “outside of $O$” together, you obtain a total that we call $\neg O$. Below, we provide a definition that is more formal (and optional, because you can take a break and come back after this parenthesis if you are saturated 🤣):

Definition: We define the operator

$\neg:\cal{O}(\mathbb{R}^2)\rightarrow\cal{O}(\mathbb{R}^2)$

by the following:

$\neg O\equiv \bigcup \{ U | U\cap O=\emptyset \}$

Now, let’s revisit the two rules of Aristotle above. If we consider the first rule, that $O$ and not $O$ is always false, it means that the intersection of those two open sets is always the empty set. I won’t show this here, but… Considering how we defined $\neg O$ above, the principle of non-contradiction is easy to establish.

For the second rule, now, what is going on? $O$ or not $O$ should always be true, which means, in a topological sense, that the union of $O$ and $\neg O$ is the whole plane $\mathbb{R}^2$. But that is clearly not the case, because, in our example, $O\cup\neg O$ is in fact:

So, this open set is the entire plane except for the unit circle! Excluding the unit circle is too much for me… 😁 Therefore, the only solution is to reject the universality of the second law: the law of excluded middle. The universe of the open subsets of the plane has its own logic and sorry Aristotle, the law of excluded middle doesn’t work here!

Indeed, the logic of the open subsets of the Euclidean plane is not satisfying the excluded middle principle.

Their logic lives in a broader, more general universe of logics: Geometric logics, or the logics of Topoi, as discovered by Lawvere, Reyes, Makkai and Joyal in the 1970s.

Facing the Paradox

When you come from a point of view of classical logic like I was, the logic of the open sets seems like a paradoxical world. What happens when you can’t use the excluded middle rule?

When I first faced the situation, I didn’t understand how this game of Venn diagrams using only open subsets could be of any interest. Probably exactly as are asking yourself right now! 😁 But hang on… I will try to show you how it’s an interesting example.

I was coming from set theory’s point of view and, in set theory, the complement of a set satisfies the two laws of Aristotle. But when you live in the world of the open subsets of the plane, the second law breaks. The complement of an open set is not open in general, as we saw. It is easy to discard that example, because it’s not satisfying what we expect!

Facing the paradox is not dismissing the paradox with futile arguments about the nature of reflexes. Had I done that, I would have missed the whole point… Facing the paradox here was about setting aside the principle of the excluded middle and seeing what would happen.

Facing the paradox was letting imagination create a broader set of theories having a logic of their own, and exploring this higher dimensional space that transcends the scope of Aristotle’s classical logic.

Facing the paradox was saying yes to all of the possible logics one can discover by studying different universes. Then, the universe of sets and classical logic switch from their universal role into that of a degenerate special case. Classical logic a dry world where absolutes live. It’s a degenerate case in the sense that the complexity of the logic collapses, in some sense. Logic loses its flavours, its ability to explain the movement and transformation of the continuous.

Everything in life is transformation and constant movement. Nothing really can reach any extreme in all the possible opposite duality pairs. Will war ever win completely over peace? Is peace an objective we can attain and maintain forever in the absolute? Clearly, this is impossible. So let’s expand our view of logic to include all this nice richness of possible colours and complexity.

This is exactly what I did in my first course of Logic. I started playing the game of changing the rules with the guidance of one of the founders of geometric logic, Gonzalo E. Reyes. His guidance through the journey of facing that paradox basically flipped all my knowledge of mathematics on its head. Mathematics have to be discovered through meditative journeys in which we get a glimpse of intuition. This inversion of focus, from external to internal logic, is what ignited that intuitive spark.

Playing the game

Now that we have seen that the law of excluded middle is not always valid and that, depending on the context, we may have to deal with a logic that doesn’t follow this principle, we are ready to look at concrete examples of how this kind of logic is richer and closer to human reality.

Let’s look at language. Linguistics already contain a much richer and more subtle logic, which can be seen with very simple examples.

In Indo-European languages at least, there are two kinds of negation. Take the following proposition:

$P=$ Peter is honest

Then, in English, there are at least two ways to negate that proposition. The first, which we will denote as $\neg P$, is the following:

$\neg P=$ Peter is dishonest

The second one is a less powerful negation, which we will denote ${\sim}P$. In English, it can be

${\sim}P=$ Peter is not honest

We clearly see that $\neg P$ is a much stronger statement about Peter than ${\sim}P$.

In fact, we can clearly see that the strong negation $\neg$ doesn’t satisfy the law of excluded middle because

Peter is honest or Peter is dishonest

is not true in general, i.e. $P\vee \neg P\neq \top$. If it were true, it would partition all humans into two absolute categories, the honest and the dishonest and this is clearly an oversimplification of reality that is not useful and is, on the contrary, socially dangerous. So, you see! You were right to discard classical logic in the first place 😂! It simply doesn’t fit with our experience of reality. At least not with the kind of reality I want to live in…

Now, to continue this exploration even further, let’s combine these two negations. For example, ${\sim}\neg P$ can be written in English as:

${\sim}\neg P=$ Peter is not dishonest

Which doesn’t mean that Peter is absolutely honest. A better interpretation of this would be:

$\diamond P\equiv {\sim}\neg P=$Peter is possibly honest

$\diamond$ is the possibility operator, and in English, you basically obtain it by combining the two negations in that specific order. We clearly get a much richer logic by not imposing the universality of the excluded middle law. These funky logics with two kinds of negations and a possibility operator may be closer to reality than we think.

In human languages, these words like “possibly” and “necessarily” are very important, and including them makes our logic much more applicable to real life.

Inclusive logic

The two negations that we discovered in the English language in the previous section, $\neg$ and $\sim$, exist in a very large universe of logics called bi-intuitionistic logics. This is a part of the whole universe of geometric logics.

When we look back at our example of the logic of the open sets of the plane $\cal{O}(\mathbb{R}^2)$, we had the $\neg$ type of negation. The $\sim$ negation doesn’t exist in the logic of the open sets $\cal{O}(\mathbb{R}^2)$.

If, on the contrary, we look at the logic of closed sets, we have the exact inverse situation: $\sim$ negation exists, but not $\neg$.

Thus, the logic you are studying is vastly influenced by the intrinsic nature of the universe. The logical operators that exist and their rules need to be contextual to the universe in question. One can then discover whether those rules are valid, instead of imposing them a priori. And, ultimately, this application will always be contextual to the mathematical, philosophical, spiritual, and scientific universe being studied.

Foundation

It takes more power to build than to burn and I want to build Hari.

Gaal Dornick, Foundation S1E1

If we are going to build a new world, a new way of living together that embraces the values of freedom and self-realization for the rest of the 21st century, we ought to propose the most durable and efficient foundation possible.

This foundation should build on the shoulders of the Ancients’ wisdom, but embrace change and the transcendence of their teachings.

This is exactly what topos theory and geometrical logic give us: a way to build upon the shoulders of the Ancients, by having sets and Boolean logic has a special case, but simultaneously including the dynamics and richness of richer, alternative logics that are closer to a reality in which we wish to embrace change.

When change becomes part of our logic, we are setting the foundation for a solid progression. The rise of consciousness will be proportional to the validity of its foundation.

For us, accepting to change the foundation is a personal choice. We will at some point have to ask ourselves, “Do I keep my illusion of the nature of the foundation, or do I keep questioning it incessantly?”